Travel Stories: The First (Female) Tour Guides of New Zealand

The Swooshing Skirt

The Swooshing Skirt

Swoosh, swoosh, swoosh ; dainty clicks and clacks that roll together to make a more flowing sound. It's a sound that has echoed off this ground for centuries, I realised as I listened to the woman wearing the swooshing skirt tell her story and that of her ancestors. She was our tour guide for an afternoon at Te Whakarewarewa a geothermal village on the North Island of New Zealand.

A tall woman, she stood strong with broad shoulders and a serious face. Her hair was pulled back into a low pony tail and she didn't boast the expressions that usually lend themselves to too many smiles. She wore the swooshing skirt over a pair of jeans and a pink T-shirt. It was quite clear the skirt wasn't her "just nipping to the supermarket" outfit, it was part of the experience. But this helped arouse my interest. I wondered on more than one occasion; what was her story? What's the story of that skirt?

Her introduction given as we stood under a tall archway offered a glimpse at what her story was - how she was a distant relative to the pioneers of tourism in New Zealand - but it sadly became clear that her words were those that she had spoken many times before. Possibly too many times. But even her heavy monotonous tone couldn't shake my fascination at what she was telling us, how Maori women have been responsible for giving guided tours of geothermal villages on the North Island of New Zealand for over two centuries. They were the first tour guides of New Zealand and they wore then - as they wear now - these handmade swooshing skirts.

The Beginning of Tourism in New Zealand

At times, my concentration slipped. It was the middle of summer in New Zealand and the sun was strong, fixed directly above my head as we walked slowly through Te Whakarewarewa. The "rotten egg" smell of the geysers that we were surrounded by grew occasionally stronger, making me think of the bad smells that would occasionally invade classrooms during my schoolday and distracting me until a gentle breeze whisked it away and cooled us down a little too. Despite my lapsing in and out of concentration and my tour guide hardly tap dancing to keep my attention, here's what I learnt:

Despite my lapsing in and out of concentration and my tour guide hardly tap dancing to keep my attention, here's what I learnt:

In the early 1800s against a backdrop of drastic changes as European settlers began to live side by side with the Maori communities already established in New Zealand, tourism was the last thing on most peoples' minds. However, a small group of women from a village close to Rotorua in the North Island began leading tours of their "thermal village" to visiting dignitaries from Europe. The trend grew to neighbouring villages including Te Whakarewarewa where tours have been led by Maori women for over 100 years.

There are other twists to the tale. The most famous guide, a half-British, half-Maori Oxbridge educated woman called Sophia saved lives in 1886 when she moved a village away from the path of an erupting volcano after she saw water levels suddenly recede in a lake she used to guide near - it was deemed nature's warning of what was to come. It was actually as a result of this volcano that her family moved to Te Whakarewarewa where she began to guide once more. Many of her descendants - male and female - work as guides in Te Whakarewarewa today.

Te Whakarewarewa

As you take your first steps into Whakarewarewa, before you begin your tour, you find yourself on a bridge. It provides a link between the ticket office and car park to the village where families live what we are assured is a normal and fairly traditional life, albeit one that features tour groups parading past your living room window every other hour. We were early meeting our tour guide so we stood on the bridge for many minutes watching local Maori children bathing and playing in the water below us. In swimming costumes, shorts and T-shirts and wearing swimming goggles they were splashing each other, smiling and shrieking in a way that only children can get away with. After some moments they looked up and noticed us, a few metres above their heads. "Throw a penny, miss! Throw us a penny!" There were imploring signs and exaggerated hand gestures. I didn't understand but was my confusion was rescued by a call to assemble; our tour was beginning.

We were early meeting our tour guide so we stood on the bridge for many minutes watching local Maori children bathing and playing in the water below us. In swimming costumes, shorts and T-shirts and wearing swimming goggles they were splashing each other, smiling and shrieking in a way that only children can get away with. After some moments they looked up and noticed us, a few metres above their heads. "Throw a penny, miss! Throw us a penny!" There were imploring signs and exaggerated hand gestures. I didn't understand but was my confusion was rescued by a call to assemble; our tour was beginning. The village itself is tiny; a small collection of houses and shops, a church, a school and a marae, a Maori gathering place where local gatherings, meetings and ceremonies take place. The main attraction has always been, like it is today, the geothermal landscape that these villages and settlements are built on and how the geysers and hot springs have shaped Maori traditions in the area. Our tour guide explained how they use the geysers to their advantage; ovens were created in the ground to cook tender meats - hangi - and sweet sponge like cakes and the water's natural heat and healing qualities were used to wash bodies and clothes. Over the years these Maori guides have shown thousands, if not millions of visitors around a village that has purposefully changed very little.

The village itself is tiny; a small collection of houses and shops, a church, a school and a marae, a Maori gathering place where local gatherings, meetings and ceremonies take place. The main attraction has always been, like it is today, the geothermal landscape that these villages and settlements are built on and how the geysers and hot springs have shaped Maori traditions in the area. Our tour guide explained how they use the geysers to their advantage; ovens were created in the ground to cook tender meats - hangi - and sweet sponge like cakes and the water's natural heat and healing qualities were used to wash bodies and clothes. Over the years these Maori guides have shown thousands, if not millions of visitors around a village that has purposefully changed very little. The Penny Divers

The Penny Divers

We followed our formidable tour guide across the bridge and again I heard the children below call out "Throw us a penny!" It all became clear quite quickly. Those children are "penny divers" and they were asking us to throw coins into the water as this was once a way for visitors to give money to the local poor children when the tours of Te Whakarewarewa first began. The children would then dive into the warm geothermal waters and retrieve as many coins as they could - most likely without the aid of swimming goggles - storing the ones they found in their mouths. The tradition has continued with these "poor children" "sometimes earning up to 100 dollars on a good weekend," our tour guide told us with a dead pan expression. I threw 20 cents in and they clambered over one another to find it; they must have thought me cheap. The tour took in most of the small village, which I have to say didn't feel as "real" as I would have liked. There were no villagers walking past, there were very few signs of life in the houses and most of the shops and a small cafe were far too tourist friendly.

The tour took in most of the small village, which I have to say didn't feel as "real" as I would have liked. There were no villagers walking past, there were very few signs of life in the houses and most of the shops and a small cafe were far too tourist friendly. I was, however, grateful for the small insights to Maori culture - their funerals are lengthy affairs with a coffin not being left alone for three days before it is finally buried - and the passion and unfaltering confidence with which our guide spoke about her heritage reaffirmed my impressions that as a country New Zealand has gone to great pains and efforts to preserve Maori traditions.

I was, however, grateful for the small insights to Maori culture - their funerals are lengthy affairs with a coffin not being left alone for three days before it is finally buried - and the passion and unfaltering confidence with which our guide spoke about her heritage reaffirmed my impressions that as a country New Zealand has gone to great pains and efforts to preserve Maori traditions.  The tour ended with us sitting down in front of a small stage where our guide showed us how the swooshing skirts were made. It was revealed as a lengthy and laborious process using a variety of leaves and plant extracts and I didn't stand a chance of making one before our time in New Zealand was to end.

The tour ended with us sitting down in front of a small stage where our guide showed us how the swooshing skirts were made. It was revealed as a lengthy and laborious process using a variety of leaves and plant extracts and I didn't stand a chance of making one before our time in New Zealand was to end. So while I don't have the skirt, my memory has still clung to the sound it made. I also doubt I'll forget the smell of the geysers and geothermal activity that inspired those pioneers of New Zealand tourism.

So while I don't have the skirt, my memory has still clung to the sound it made. I also doubt I'll forget the smell of the geysers and geothermal activity that inspired those pioneers of New Zealand tourism.

Before our tour was over I asked our guide why it was that traditionally women are tour guides, rather than the men of the community. The answer I got was a rather blunt and possibly historically inaccurate "Why not?". This may not have given me the revelatory and revolutionary explanation I was looking for, but it was an answer I couldn't disagree with nor be displeased by. PS If you would like to know why I didn't take a photo of this enigmatic woman it's because when I said she was formidable and serious, I actually meant she was very, very scary.

PS If you would like to know why I didn't take a photo of this enigmatic woman it's because when I said she was formidable and serious, I actually meant she was very, very scary.

P.P.S Whakarewarewa is pronounced Phu-ka-rewa-rewa (yes, really) and here is the website for their tours.

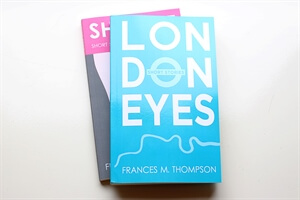

Frances M. Thompson

Find Frankie on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and Google+.

Family Travel: How to Travel with Kids - My Golden Rules

Family Travel: How to Travel with Kids - My Golden Rules_x300.jpg?v=1) Amsterdam Travel: Best Luxury Hotels in Amsterdam - Reviewed!

Amsterdam Travel: Best Luxury Hotels in Amsterdam - Reviewed! Solo Luxury Travel: Best Caribbean Islands for Solo Travellers

Solo Luxury Travel: Best Caribbean Islands for Solo Travellers New Zealand Travel: 51 Interesting Facts About New Zealand Aotearoa

New Zealand Travel: 51 Interesting Facts About New Zealand Aotearoa Amsterdam Travel: Accessible Travel Guide for Amsterdam

Amsterdam Travel: Accessible Travel Guide for Amsterdam About the Blog & Frankie

About the Blog & Frankie Welcome to My Amsterdam Travel Blog!

Welcome to My Amsterdam Travel Blog! Welcome to My Luxury Family Travel Blog!

Welcome to My Luxury Family Travel Blog! Welcome to My Writing Blog!

Welcome to My Writing Blog! Lover Mother Other: Poems - Out Now!

Lover Mother Other: Poems - Out Now! I Write Stories That Move You

I Write Stories That Move You Order WriteNOW Cards - Affirmation Cards for Writers

Order WriteNOW Cards - Affirmation Cards for Writers Work With Me

Work With Me